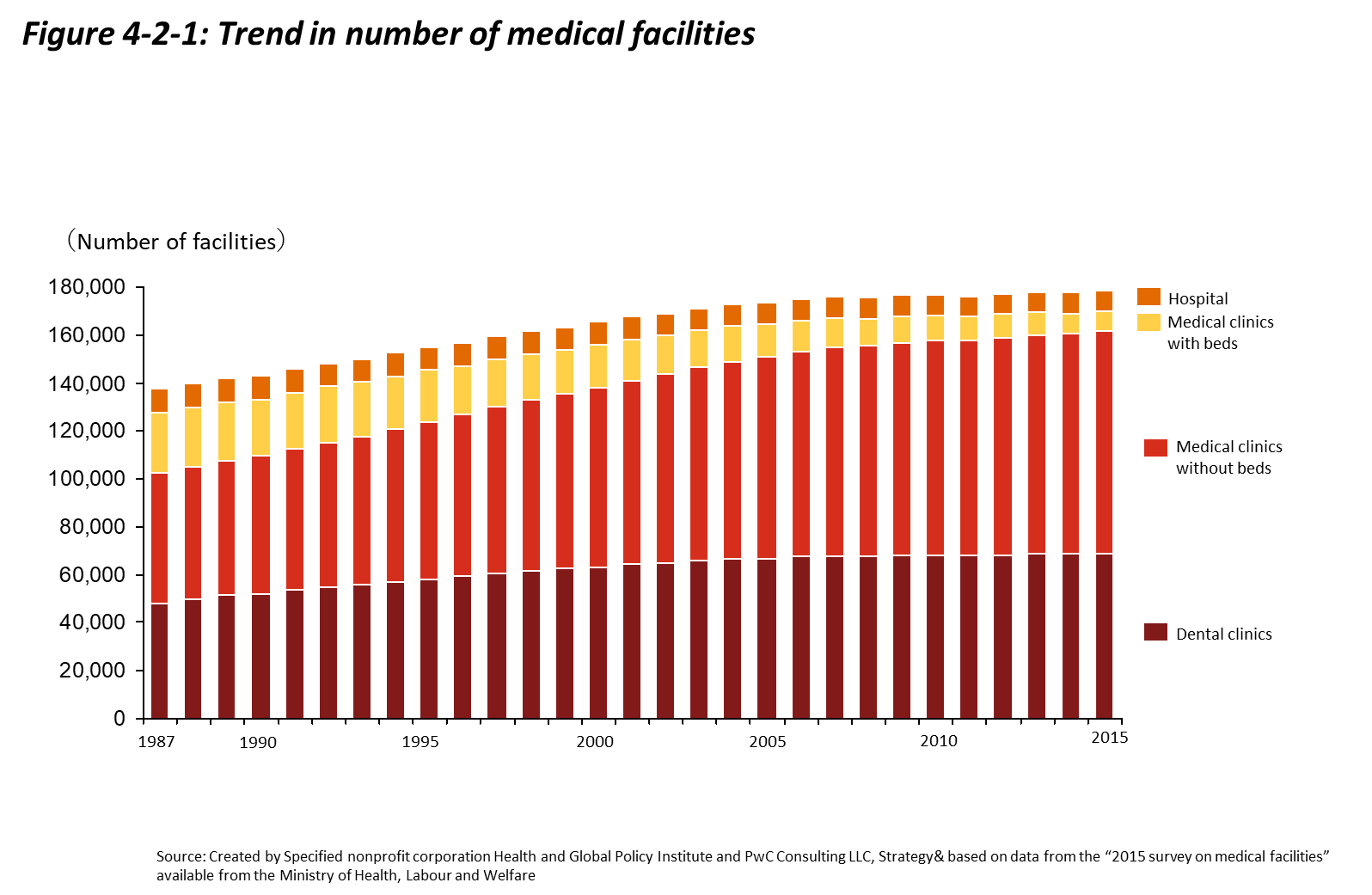

Medical facilities in Japan can be divided into medical clinics (inpatient/outpatient), dental clinics, and hospitals. As can also be seen from Figure 4-2-1, medical clinics account for most medical facilities.

4.2 Classification of Medical Facilities and Hospital Beds in Japan

Hospitals and medical clinics are distinguished in Japan based on their numbers of beds. Facilities with 20 or more beds are referred to as “hospitals,” while facilities with 19 or fewer beds or lacking in-patient accommodations are referred to as “clinics.” As of 2015, Japan had 8,480 hospitals, 7,961 in-patient medical clinics, 93,034 out-patient clinics, and 68,737 dental clinics. Looking at the changes in medical facilities from 1987 to 2015, the number of hospitals declined by a factor of 0.86, while the number of out-patient clinics grew by a factor of 1.7.[2]

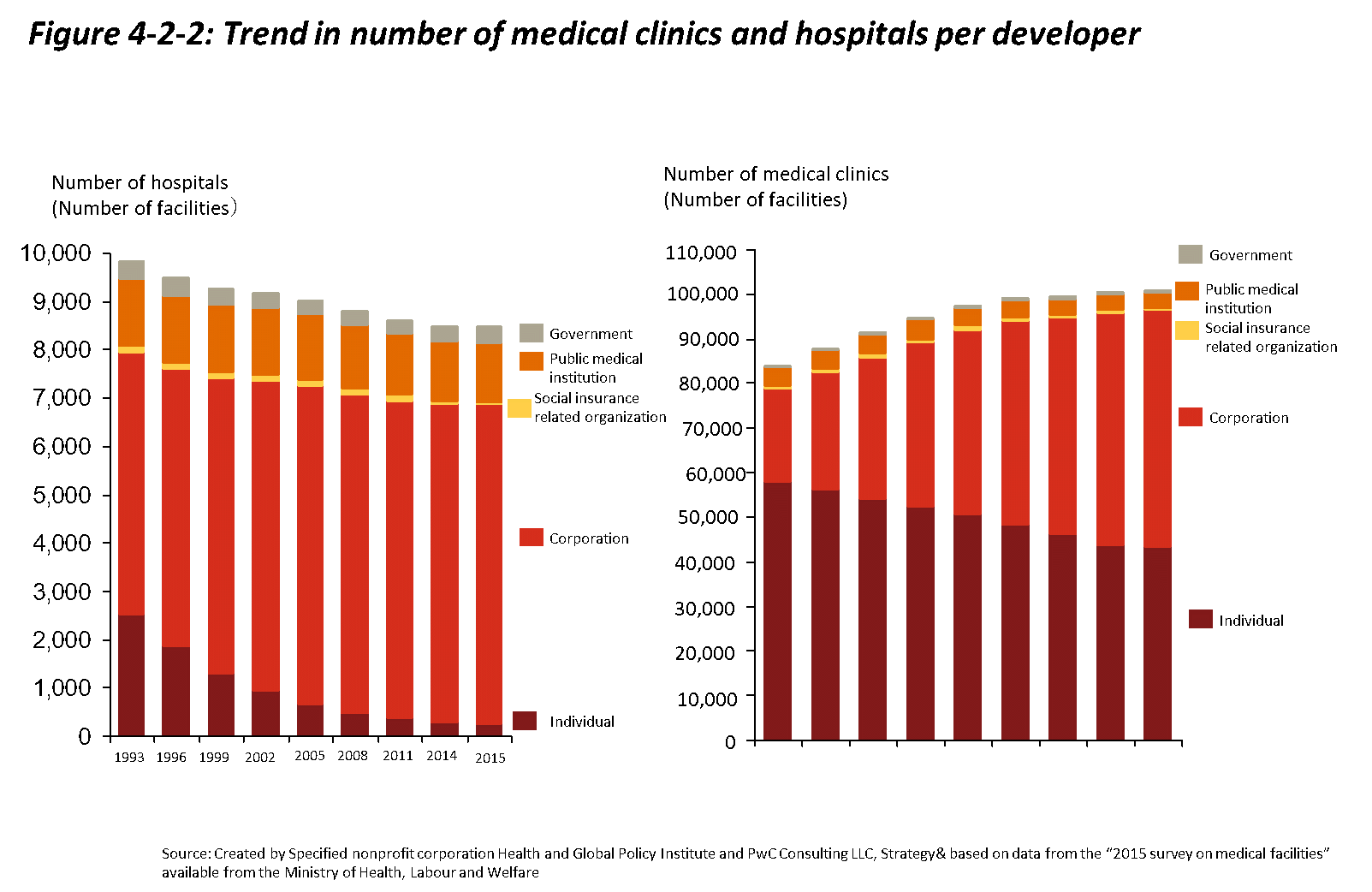

Hospitals and clinics can be broadly categorized by the organizations that manage them. There are national, public, social insurance organization, corporate, and private facilities, among others. As can also be seen from Figure 4-2-2, private hospitals continue to be the main healthcare provider within Japan’s healthcare delivery system, but corporate clinics are gaining prominence. This characteristic of Japan’s healthcare delivery system is unique, since the majority of hospitals in other countries such as the United Kingdom and France are public facilities.[3]

The types of hospitals operating in Japan include general hospitals, advanced treatment hospitals, regional support hospitals, clinical research hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, and tuberculosis hospitals. Among these, advanced treatment hospitals, regional support hospitals, and clinical research hospitals have requirements that vary from those of general hospitals regarding matters such as staffing. Only hospitals that fulfill these requirements may be licensed to operate.[4]

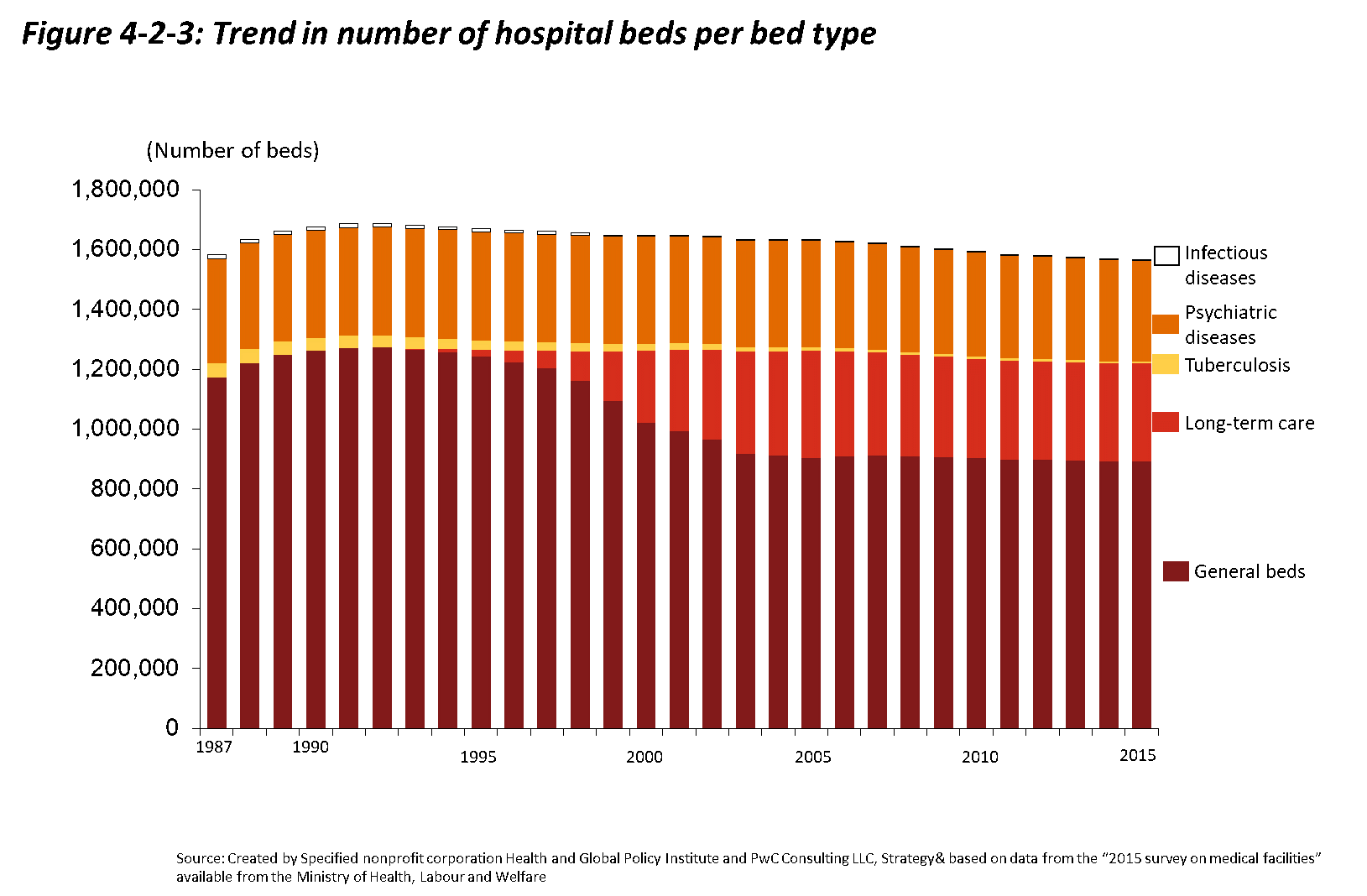

Hospital beds in Japan are classified as general beds, long-term care beds, psychiatric beds, infectious disease beds, and tuberculosis beds[5]. Although prior to the 4th revision of the Medical Care Act in 2000, “long-term care beds” and “general beds” were combined in a single category referred to as “other beds,” this category was split to facilitate more circumstance-appropriate healthcare delivery. As can be seen in Figure 4-2-3, most hospital beds are general beds.

In terms of general hospital bed trends, due to healthcare expense burden mitigation measures implemented after the achievement of universal health coverage such as the High-Cost Medical Expense Benefit System, public demand for medical care increased, and in accordance, the numbers of hospitals and hospital beds increased as well. It is also worth noting the reality that general hospital bed numbers are propped up by many “socially hospitalized” patients who are unable to leave hospitals and return home due to financial hardships or other reasons.[6]

By 2025, all members of the Baby Boomer generation (those born between 1947 and 1949), will reach age 75 or over, inducing sharp increases in social security costs, including long-term care expenditures and medical care expenditures. With the aging of the Japanese population predicted to progress even more rapidly in the future, it is important for Japan to effectively utilize its limited medical resources. To ensure patients are able to access appropriate care at the appropriate facility regardless of their location or situation, the government is functionally differentiating medical facility beds according to needs, aiming to reduce the number of hospital beds to between 1.15 and 1.19 million by 2025.

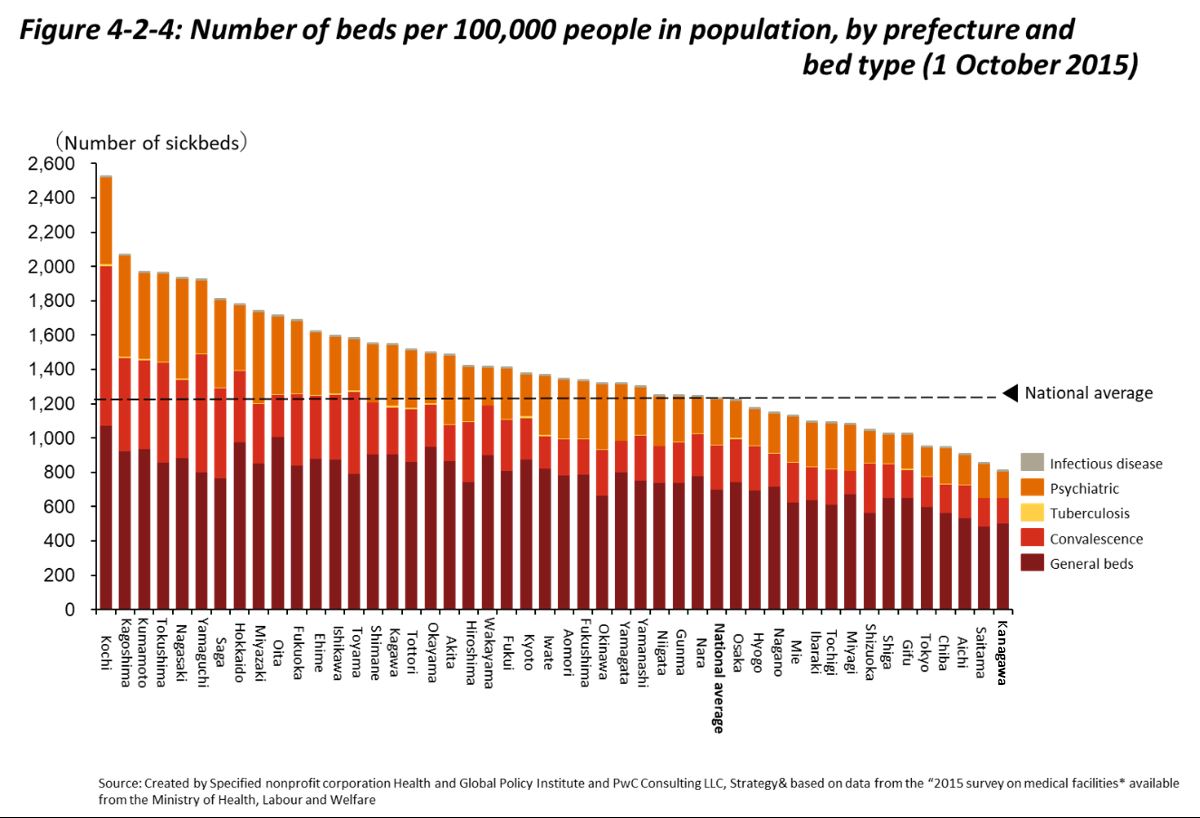

As shown in Figure 4-2-4, there are large disparities among prefectures in terms of the number of hospital beds. The number of hospital beds per 100,000 people is about three times higher in Kochi Prefecture, where it is the highest, than in Kanagawa Prefecture, where it is the lowest. In efforts to realize a more ideal future healthcare delivery system, Japan is addressing such regional disparities by formulating Regional Medical Care Visions (See Section 4.4) and reporting hospital bed functions and needs to prefectural governors.

References

[1] Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare “Current Situation and Issues Regarding the Healthcare Provision System” http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12601000-Seisakutoukatsukan-Sanjikanshitsu_Shakaihoshoutantou/0000184301.pdf (Accessed 2018, Feb.1)

[2] Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare “Survey of Medical Facilities” http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/15/dl/02_01.pdf (Accessed 2017, Nov.20)

[3] Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare “Survey Research Regarding the Actual Situation of Medical Corporations Outside of Japan” http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iryou/igyou/igyoukeiei/anteika.html (Accessed 2017, Nov.20)

[4] Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare “Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2015 Fiscal Year Edition White Papers ” http://www.mhlw.go.jp/wp/hakusyo/kousei/17-2/dl/02.pdf (Accessed 2017, Nov.27)

[5] Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare “Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2015 Fiscal Year Edition White Papers ” http://www.mhlw.go.jp/wp/hakusyo/kousei/17-2/dl/02.pdf (Accessed 2017, Nov.27)

[6] National Federation of Health Insurance Societies (2017) Healthcare Coverage Seen Through Charts, 2017 Edition,” Gyosei Corporation, p.43