The Constitution of Japan, created in 1946 and implemented in 1947, laid the foundation for Japan’s parliamentary system of government, which is divided into three branches: the legislative branch, the executive branch, and the judicial branch. Power is separate and checks and balances exist between the three branches.

Government Structure

The Legislative Branch

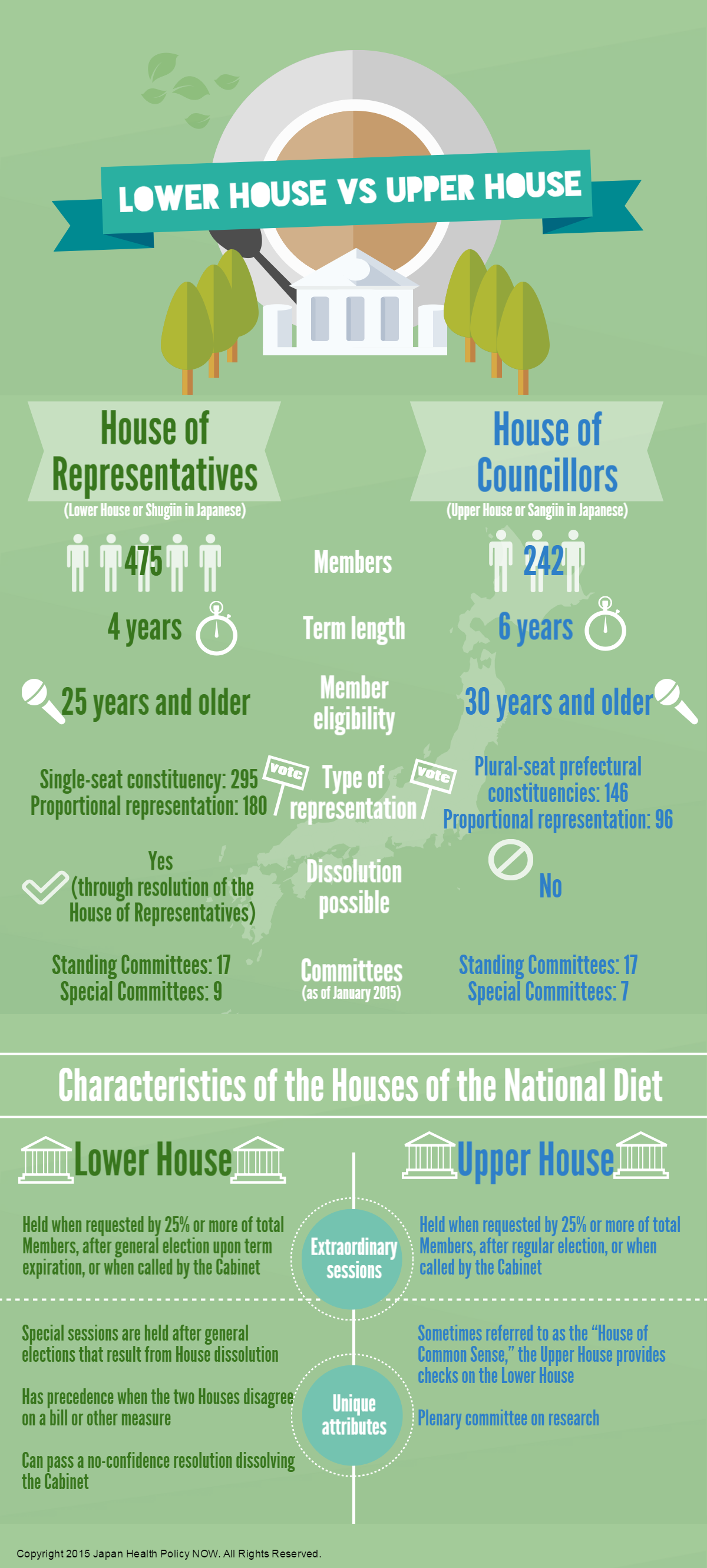

The legislative branch is comprised of the country’s sole law-making body, the National Diet. The Diet has two Houses, the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors, both comprised of members elected by the public. Members of each House are required to serve on at least one standing committee during ordinary sessions, which begin in January and last 150 days with one possible extension.

Frequent National Elections

In Japan, national elections frequently take place. If we take into account Parliamentary (Diet) elections, there were 7 elections between 2005 and 2015, which means there was an election once every 1.5 years. Lower House elections are held so frequently (once every 2.5 years over the past 10 years) that it is not uncommon for Members of the Lower House to leave office without completing a full four year term. In addition, every three years, an election is held for half of the Upper House. This election has significant impact as it serves as a mid-term evaluation of the administration. Add to this local elections held nation-wide every four years and elections to determine the heads of the majority and minority political parties, the number of elections further increases.

As a result, the government, the ruling party, and each political party must pay critical attention to elections, which leads to a certain level of instability in politics and, what some consider, an easy avenue for the influential voices of older persons to affect policy.

The Executive Branch

The executive branch is led by the Prime Minister, who is nominated through a Diet resolution followed by official appointment by the Emperor. The Prime Minister’s office is supported by the Cabinet, which is comprised of Cabinet Ministers and Cabinet State Ministers who are designated by the Prime Minister. These Ministers remain in office until they are dismissed by the Prime Minister or the Lower House passes a no-confidence resolution (or rejects a confidence resolution) dissolving the entire Cabinet including the Prime Minister. A no-confidence resolution of the Cabinet does not result in dissolution when the Lower House is dissolved within ten days of the resolution.1 The Cabinet includes the Cabinet Office, Cabinet Agencies, and 11 Ministries, including the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare and the Ministry of Finance. These central government offices (chuo shocho) steer Japan through implementation of various policies and Cabinet-initiated legislation.2

The Judicial Branch

The judicial branch is comprised of the Supreme Court and four types of lower courts. The Supreme Court ensures that legislation and actions taken by the Cabinet and the Diet are constitutional. The Supreme Court’s chief justice is appointed by Cabinet nomination and official appointment by the Emperor. The other 14 justices are appointed by the Cabinet. Justice appointments are reviewed periodically within the House of Representatives and can be terminated through a majority vote, although this has yet to happen. Mandatory retirement age of Supreme Court justices is 70. The current Chief Justice is Itsuro Terada, who was made Chief Justice in April 2014.

Below the Supreme Court are high courts, district courts, family courts, and summary courts. Most trials involve one to three judges. In 2009, criminal trials began to include the general public through the use of lay judges.3

Cabinet-led Policy Making

Japanese government and policy making was once known as “bureaucrat-led.” Each ministry along with LDP-backed special-interest legislators* dominated policy discussions and policy making processes. This all changed with the 2001 election of Junichiro Koizumi as Prime Minister. Prime Minister Koizumi firmly opposed such special interest legislators and unfair ministry intrusion leading to a transformation of this long standing trend. By occasionally disregarding the ideas of the LDP and Ministry officials, he was able to take the lead in the appointment of Cabinet Ministers and on critical policy decisions. The bureaucratic influence began to fade and a new era, which continues today, of Cabinet-led policy making was born. While critical policy is decided at the Cabinet level, as opposed to at the MHLW, the influence of special-interest legislators is still strong.

*This term refers to Diet members who have strong ties to a specific ministry or with specialized knowledge in one policy area. For example, Diet members who are especially familiar with the work of the MHLW would be known as MHLW legislators. Many times, these legislators, whose influence remains strong, lead the health and welfare committee within the LDP or have experience as the Health Minister or Vice-Health Minister.

References

1 Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Election System in Japan.http://www.soumu.go.jp/senkyo/senkyo_s/naruhodo/naruhodo03.html#chapter1 (accessed on July 30, 2015)

2 The Cabinet Office, Outline of Duties 2014. http://www.cao.go.jp/en/pmf_index-e.html (accessed on July 30, 2015)

3 Courts in Japan. Lay Judge System. http://www.saibanin.courts.go.jp (accessed on July 30, 2015)